We’re continuing last week’s discussion about interpreting water test results.

PROBLEM: Alkalinity is arguably the most important water quality factor to monitor and manage when growing greenhouse crops, but it’s not the only factor that requires special attention and care. If you missed the last tip on Understanding Alkalinity and Managing Too-low Alkalinity, check out last week’s tip.

NICK’S TIP: This week, we’ll focus on other key water quality parameters, and how to interpret and manage them when reviewing water test results.

Soluble Salts

It’s critical to factor your water’s baseline electrical conductivity (EC) into crop management decisions. Whether you’re troubleshooting issues with EC-sensitive crops or performing routine maintenance like fertilizer injector calibration, a current, accurate EC reading is needed to ensure you are taking appropriate action. Most often reported in mS/cm (millisiemens per centimeter), EC is a measure of how many ions (like Ca2+, K+, Mg2+, NO3–, NH4+, etc.) are present in your water. Pure water is not a good conductor of electricity on its own, but ions (such as salts) dissolved in water increase its ability to do so. The higher the EC value, the more ions are present.

• Ideally, your water’s EC should be below 0.5 mS/cm for plug and liner production. Young plants grown with water that has an EC much above 0.5 mS/cm often experience issues due to salt accumulation in the growing media. When young plants are grown using above-optimal EC water, ions present in your water and ones added via fertilizer can build up and burn roots, stunt growth or open the door for disease. Monitor growing media EC regularly and leach with clear water as needed to avoid damage to plugs and liners.

• Many finished crops can be grown with few issues using water that has an EC as high as about 0.8 mS/cm, and some can even tolerate a baseline EC of up to 1.0. However, using water with a lower EC is almost always better and reduces the chance of complications. New Guinea impatiens, for example, can become stunted and distorted when soil EC is above ~1.5 mS/cm for extended periods. If your water’s baseline EC is 1.0 and fertilizer adds 1.14 mS/cm when mixed at 150 ppm N, you’re applying a solution with a total EC of 2.14 mS/cm each time you feed the crop. When applied enough times without a clear water leach in between, the growing media’s EC can climb and potentially cause issues.

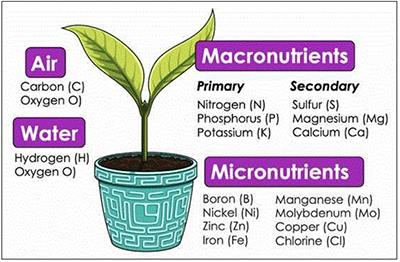

Macro- and Micronutrient Levels

Thorough water tests provide readouts for most (if not all) essential mineral nutrients for plant growth. Understanding which mineral nutrients are already present in your water is critical when choosing fertilizers or investigating odd, abiotic symptoms that appear in your crops.

• Water test reports should include nitrogen (N; ideally nitrate-, ammonium- and urea-forms), phosphorous (elemental P & soluble P2O5), potassium (elemental K & soluble K2O), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sulfur (elemental S & soluble SO4), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), boron (B), copper (Cu), molybdenum (Mo), zinc (Zn), sodium (Na), chloride (Cl) and aluminum (Al).

• If one or more macro- or micronutrients is in abundance or out of balance in your water, select a fertilizer formulation that will help balance what’s already present with what you still need to provide for good growth. Sometimes this is difficult or impossible solely using commercially available fertilizers — instead, you need a custom blend from your supplier.

• Depending on the nutrient and how over- or underabundant it is in your water, more drastic management measures may be necessary. For example, excessively high levels of boron (B) may make producing floriculture crops very difficult (or even impossible!) and installing a reverse-osmosis system may be necessary to correct the issue.

• Another option is a fertilizer system that automatically adjust or that can be manually tuned to add individual macro- and micronutrients based on continuous sensor reading. However, these are often expensive investments and costly to maintain, so large growers are typically the only operations that utilize them.

• If surface water is your primary source, macro- and micronutrient concentrations should be monitored regularly — especially if you have a closed or recirculating irrigation system. Monthly macro- and micronutrient tests should be your minimum goal when irrigating from a retention pond, reservoir or other surface water source.

• Mineral nutrient levels in most municipal water supplies remain stable over time but this is not always the case, so you should perform twice-yearly water testing, at a minimum. In some cities, you can request periodical readouts from your municipal water supplier free of charge. While the report they send is rarely a full irrigation water report, major changes in concentrations of specific ions that they do report can serve as good indicators that you may need to adjust your feed program or have a more comprehensive test performed to get in front of potential issues.

Water pH

While not as important a standalone factor as alkalinity, your water’s pH (how acidic or basic it is) can serve as an indicator of water quality changes. This is one of those “a square is always a rectangle, but a rectangle is not always a square,” situations.

High alkalinity often correlates with higher water pH (generally above about 7.0) on a test report, but high pH alone does not necessarily indicate high alkalinity.

It’s critical to look at pH and alkalinity together to make fertilizer and other crop culture decisions. A good irrigation water test always includes both pH and alkalinity.

If you perform regular pH and EC tests on your raw water in-house, a sudden increase in pH can serve as a good indicator that your water quality is changing and a more in-depth test should be performed ASAP.